Move Faster

Why speed matters and why it's more than just timing.

You are probably too slow. I’m probably too slow.

We tend to treat AI speed as a vanity metric—a way to spend less time on the boring stuff or fit more work into a roadmap. But speed isn’t just about doing more of the same thing. When you cross a certain threshold of velocity, the fundamental physics of how you build things changes. It changes how you make decisions, how you view code, and where you spend your mental energy.

It’s not magic; it still takes skill to maintain taste and quality at 100mph. But once you get in the habit of Think → Automate consistently, you stop just asking “How can I do this in less time?” and start asking “How does this change what is worth doing?”.

In this post, I wanted to collect some thoughts on why speed matters1 and the second-order consequences of consistent effective automation.

With Speed…

You can make fewer decisions.

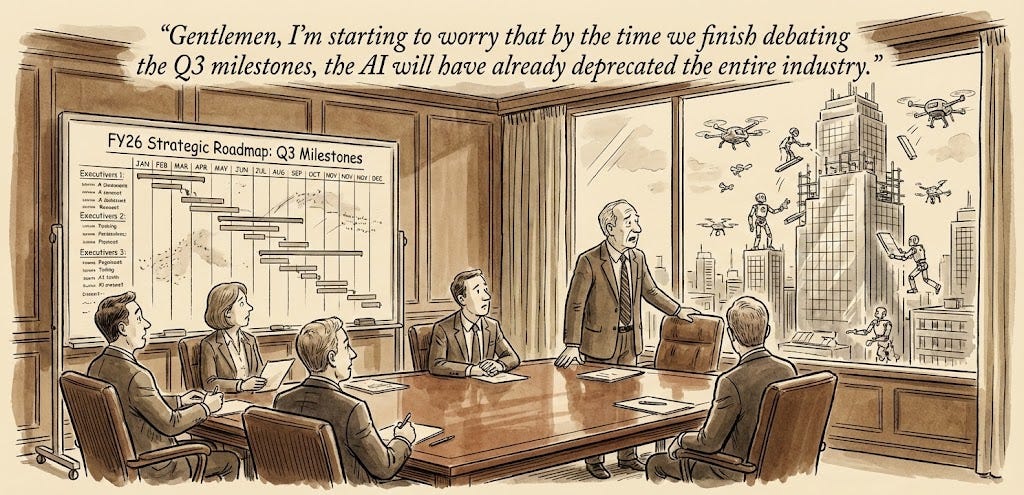

You stop debating which feature to build because prediction is expensive, but verification is cheap. In the old world, you had to guess the winner in a conference room. In the new world, you build three divergent approaches simultaneously and let the results decide. The cost of debating the work becomes higher than the cost of just doing it.

Speed also eliminates the agonizing prioritization of small tasks. Every person has a mental threshold for “worth fixing”—we ignore bugs that take hours to fix but offer little value. When the cost of execution collapses to near-zero, that threshold vanishes. You stop managing a backlog based on effort and start fixing problems purely based on impact.

You can trade assets with consumables.

The ROI threshold for software or other assets collapses. You begin building "single-use software" (a dashboard used for one week during Q4 planning, or a complex script for a single customer) and then delete it. Code stops being an Asset (something you maintain, refactor, and cherish) and becomes a Consumable (something you generate, use, and discard). This logic extends to roles and systems, where you trade permanent fixtures for instantaneous solutions. In a slow world, analyst is a permanent role because answering complex questions is hard and ongoing; in a fast world, you don't hire an “analyst”2 but maintain a system (context and infrastructure) for answering questions instantly. The role or specialization exists only as long as the problem does.

(See also Most Code is Just Cache)

You can swap plotting for steering.

When execution takes months, you need a map. You need to tell the higher ups what you will be doing in Q4 so you can hire for it in Q1. But if you can build anything in an week, a X-month roadmap is a liability, it locks you into assumptions that will be obsolete in X days. In a slow world, we write PRDs and mockups because they are cheaper than code. We try to simulate the future in a Google Doc to avoid building the wrong thing. With speed, the "imagination gap" disappears. You stop arguing about how a feature might work and start arguing about the actual working feature.

You can work on the derivative.

Most of what you spend time doing today, you will not be doing in five years. When a task takes 4 hours, your brain is occupied by the execution—the “velocity”. When that same task is automated to take 4 occupied seconds, your brain is forced to shift to the “acceleration”. You stop fixing the specific bug; you fix the rule that allowed the bug.

With general intelligence, you can go a layer deeper: you can accelerate the acceleration. You don’t just write the prompt that fixes the code; you build the evaluation pipeline that automatically optimizes the prompts. You stop working on the work, and start working on the optimization of the work. You shift from First-Order execution (doing the thing), to Second-Order automation (improving the system), to Third-Order meta-optimization (automating the improvement of the system). AI eats the lower derivatives, constantly pushing you up the stack to become the architect of the machine that builds the machine.

You can learn faster than you decay.

In the old world, 'measure twice, cut once' was virtuous because construction was expensive. In the new world, the cost of a wrong hypothesis is near-zero, but the cost of obsolescence is incredibly high. If a project takes six months to ship, you risk solving a problem that no longer exists with tools that are already outdated. This speed also hacks probability. Even if you are brilliant, some percentage of your decisions are guaranteed to be wrong due to hidden variables. By moving fast, you increase your “luck surface area”3. You take more shots on goal, test more hypotheses, and stumble into more happy accidents.

So…

Find derivative thinkers

Look for people whose identity isn’t tied to a specific task but to the rate of change of their output. They are never doing the same thing they were doing six months ago because they have already systemized that role away. The divide between those who “get it” and those who don’t is widening4; the former are architects of their own obsolescence, while the latter repeat the same loop until AI automates it for them. The former view repetitive effort as a personal failure, willing to spend time automating a one-hour task just to ensure they and no one else have to do it again.

Automate everything

You can’t leave anything on the table. This is Amdahl’s Law for AI transformation: as the “core” work approaches zero duration, the “trivial” manual steps you ignored—the 10-minute deploy, the manual data entry on a UI, the waiting for CI—become the entire bottleneck. The speed of your system is no longer determined by how fast you code, but by the one thing you didn’t automate5. If an agent can fix a bug in 5 minutes but it takes 3 days for Security to review the text or 2 days for Design to approve the padding, the organization has become the bug. You need to treat organizational latency with the same severity you treat server latency.

Practice destruction

When creating is free, the volume of mediocre “things” approaches infinity. To survive, you must simultaneously raise your taste and lower your sentiment. You need the taste to look at ten AI-generated approaches and intuitively know which nine are subtle garbage. And you need the destructive discipline to delete the code you generated last week because it has served its purpose. We are biologically wired to hoard what we build (see IKEA effect), but in an age of infinite generation, hoarding leads to complexity, and complexity kills speed. If you automate the building but not the pruning, you won’t get faster; you will drown in a swamp of your own AI slop.

Tax the debate and the review

Diverse opinions are vital. But we need to change where the disagreement happens. In the old world, we argued in rooms about predictions (”I think users will want X”) and held tedious reviews to catch errors. In the new world, a manual review is just a manifestation of a lack of automation in creation. Instead of reviewing the output, you should be debating the system that created it. If you are constantly reviewing the same class of errors, stop reviewing the code and start fixing the context that generated it. Stop debating which decision predicts the future and start debating the system and its actual outputs. Shift the expertise from the end of the process (critique) to the beginning (system design).

Move faster

We are conditioned to expect friction, to wait for builds, to schedule meetings, to "sleep on it". When intelligence is on tap and initiation is near-instant, waiting starts to become a choice, not a necessity. In a slow world, we use the "waiting time" of the process to subsidize our own lack of clarity. In a fast world, that subsidy is gone. If you aren't moving, it's not because the system is compiling; it's because you don't know what to do next.

I originally planned to call this post “Why Speed Matters” but as I was finalizing it, I actually found this other great article: “Why Speed Matters” by Daniel Lemire which has a similar set of arguments for velocity (especially for the “You can learn faster than you decay.” section).

To be clear the people who were former “analysts” are the ones best suited to build and maintain this new system. They would now be working at the ‘derivative’ of making the system better at ‘analyzing’ without being in the loop.

I really align with how Zara discusses luck in “How to get lucky in your career”. You could say Luck = surface area × probability = the number of opportunities you (or AI) create × the likelihood of any one opportunity paying off.

Illustrated literally by Rahul’s tweet on CI times becoming a bottleneck for SWE.

The framing of First-Order to Third-Order thinking is super useful. I've been experiencing this shift firsthand where the bottleneck moved from coding to waiting for organizational processes. The Amdahls Law analogy for org latency is spot on. One thing I'd add is that this also changes how we estimate work. Traditional story points dont capture when the cognitive load shifts entirely to system design.