Understanding AI Benchmarks

Tips for interpreting frontier model releases and their SOTA benchmark scores.

Despite being the highlight of every major launch, benchmarks are the most widely misunderstood part of the AI ecosystem.

Every few weeks, we get a new press release featuring a bar chart where the new model conveniently towers over the previous state-of-the-art—whether it’s Anthropic’s Claude Opus 4.5, OpenAI’s GPT-5.2 or Google’s Gemini 3. The narrative is always “Number Go Up,” implying a universal increase in intelligence.

In this post, I want to demystify how these benchmarks actually work, expose where they are misleading, and dig into the specific popular evaluations you’ll see in launch posts. This post was inspired by the many confused Kalshi/Polymarket comments on recent AI benchmark markets.

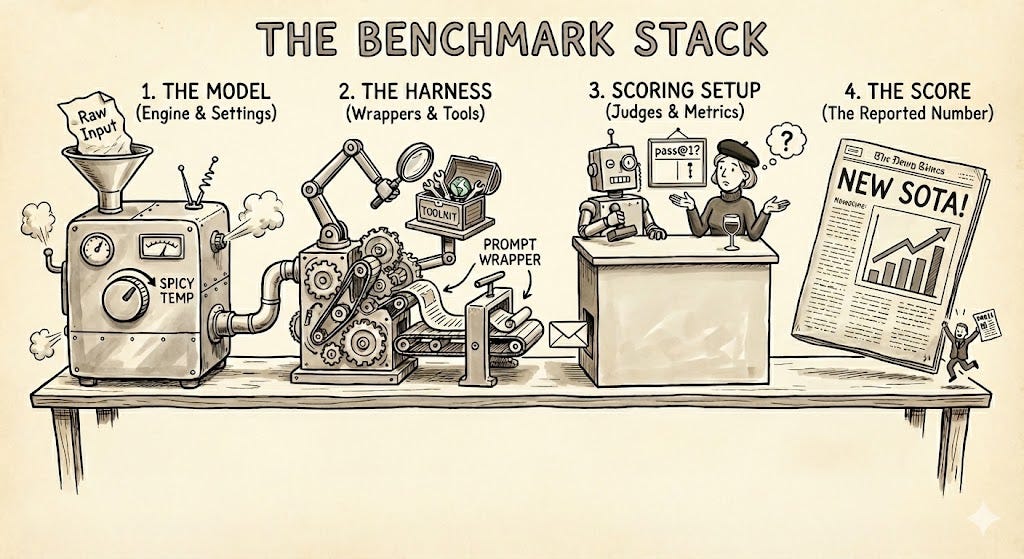

The Benchmark Stack

When we talk about a model’s performance, we are rarely talking about the raw model weights in isolation. A benchmark score is the output of a specific function: f(model, settings, harness, scoring). If you change any variable in that tuple, the score changes—often dramatically. To understand why a model “wins,” you have to look at the entire stack.

The Model — We tend to use shorthand names like “GPT-5.2” or “Claude 4.5 Sonnet,” but in the context of a benchmark, you are really measuring a specific combination of runtime settings.

Sampling Settings: Parameters like temperature, top_p, and max_tokens fundamentally change how the output of the model is encoded into text.

Reasoning Strength: A model often performs differently depending on its “thinking budget.” You will increasingly see suffixes like

-xhighor-16k-thinkingdenoting a specific configuration where the model is allowed to generate reasoning tokens before responding or using a tool.

The Harness — This is the code that wraps the model to facilitate the test. At the end of the day, LLMs are still text+image -in/text -out, so a harness is required to translate "solve this issue" into actual API calls.

Tools: Does the harness allow the model to use a coding environment to test or calculate things before answering? Does it provide internet search access? Are the tool schemas well defined and do they return intuitive responses?

Prompting: Are the system prompts vague or specific? Do they include examples (aka few-shot)? Are the provided instructions and constraints consistent?

Implementation: Are we running the model in a agentic tool-loop or just taking the first output? Are we post-processing structured outputs or counting minor formatting errors as hard failures? Do we structure the problem as an append-only conversation or do something else?

The Scoring Setup — How we grade the model can be just as critical as the model itself. This comes down to what we count (the metric) and who does the counting (the judge).

The Pass: You’ll see pass@k which means “did it get it right with K chances” (commonly “pass@1”) or pass^k which often means “did it get it right consistently K independent times” (much harder).

The Judges (Programmatic vs. LLM): Programmatic judges (unit tests, regex, exact-matches-ground-truth-answer) are objective but brittle—a correct code snippet formatted slightly wrong gets a zero. LLM-as-a-Judge captures nuance but introduces potential bias and indeterminism.

My bet would be that if you just varied each of these independently just a bit, it would completely re-arrange the top-5 for most benchmarks.

It’s hard for me to take benchmarks too seriously that don’t have an agentic harness (i.e. the model can execute code and tools in order to solve a task) or reasoning enabled since those are becoming fundamental to how modern LLMs solve tasks.

Misleading Scores

Benchmark scores are often noisy estimates, not precise measurements. When a new model claims to beat by x%, the significance of that margin evaporates when you look closer at how it might’ve been measured. From reading the footnotes of releases over the past few years and digging through benchmark source code, I’ve found a decent number unintuitive practices.

Measurement Noise — Benchmarks are treated like precise instruments, but the process of measuring model performance is often surprisingly fragile and inconsistent.

Broken Tests: The code powering these benchmarks is often written by researchers, and "research code" tends to be... scrappy. It is not uncommon for a “failure” to actually be a bug in the test runner, or for a correct solution to be rejected because the regex was too strict. It’s also possible for certain model provider scores to be handicapped due to API errors and rate limits that occurred during evaluation.

Variance: LLMs often act stochastic even with fixed seeds and decoding settings. Just running the exact model stack several times could sway certain benchmarks several percentage points. You may sometimes seen confidence intervals but it’s still extremely common to not report them.

Funky Reporting — Labs are under immense pressure to show state-of-the-art performance and each choose slightly different ways to report metrics. These differences can be quite misleading for folks looking for an apples-to-apples comparison.

Multi-pass Variability: Labs may report different k-values for a pass@k benchmark that may mislead folks comparing values across model releases by different release posts.

Harness Tweaking: Labs sometimes modify the benchmark code itself. This can range from "fixing" (deleting) test cases they deem unfair, to appending system prompts specifically designed to guide the model through that specific test's quirks. They may also modify the harness to leverage parallel test-time compute (this is different from multi-pass variability in that the consensus of the agents is used as the score for a single run rather than just picking the best run after the fact).

Stale Baselines: Some benchmarks change overtime due to bug fixes, fresh data, or even provider-side API stability fixes. Comparing a brand new model against a competitor’s reported score from X months ago might not be an identical comparison.

Real Life Discrepancies — The model that gets benchmarked might not act like the model you experience in production.

Model Mismatch: The version of the model used to evaluate might not be identical to the one released on the API. This could be due to differences between a pre-release and release checkpoint caused by alignment-tuning, quantization, or even inference hardware differences.

Efficiency Blindspots: Most benchmark score reports don’t come with latency and cost. Especially in high reasoning and parallel-compute setups these can pose meaningfully extreme trade-offs between intelligence and what’s actually feasible in a production application.

Contamination: It’s very difficult to truly guarantee a model never saw questions or answers from benchmarks during training. There are plenty of techniques used to avoid obvious cases of this (e.g. canary strings), but it’s a bit of a grey area if/when these labs adjust training datasets to mirror benchmark adjacent-tasks.

Unscored Failures: Benchmarks often check for the presence of a correct answer, not the absence of a side effect. A coding agent that deletes your database and then returns the correct code to pass tests still “passes” the benchmark.

So yeah… there’s a lot of ways benchmarks can be broken.

Benchmarks

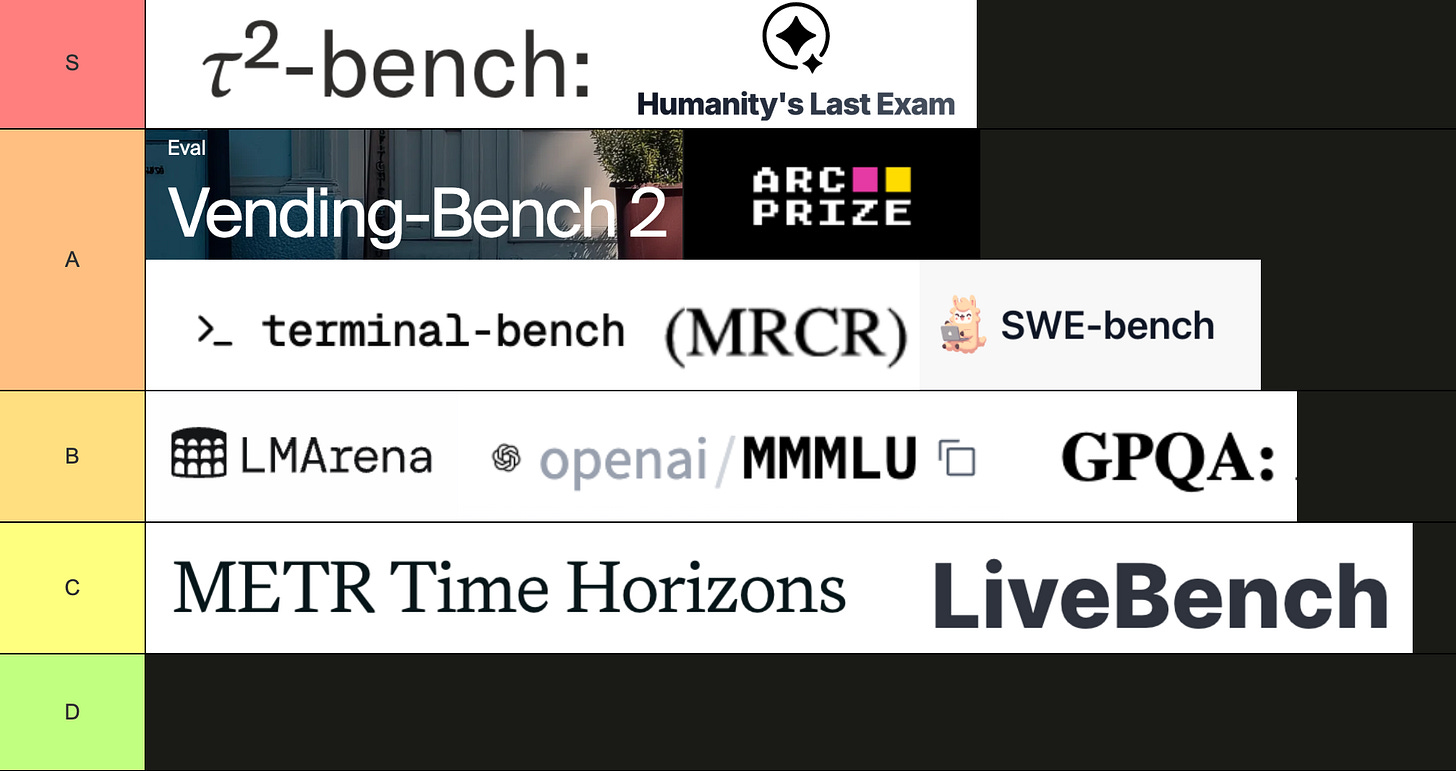

Some takes on several popular benchmarks1. Pros and cons are my subjective opinions around what I consider makes a high-signal interpretable benchmark.

LMArena (Text Arena)

A crowdsourced platform where users prompt two anonymous models side-by-side and vote on the better response. Instead of relying on static expert examples, it captures human “vibes”—measuring general helpfulness and text response usefulness—and uses a Bradley-Terry statistical model to convert these head-to-head votes into a ranked Elo rating (somewhat similar to Elo systems in video games and chess).

The main flaw (besides saturation) is the gap between the product and the model. When you use LMArena, you aren't testing Claude.ai against ChatGPT; you are testing the raw LLM with a fairly generic "You are a helpful assistant" system prompt. It measures the default behavior of these models which isn’t really how most interact with them. Despite this it’s a decent signal for the “popular vote” in the LLM space.

Pros: It is a rolling benchmark (always updating), directly measures human preference, and allows for style control.

Cons: The data is bloated by bad/easy questions (leading to saturation), it is prone to unfair lab testing (see The Leaderboard Illusion), and it is purely simple chat-based (as opposed to agentic). The scores are relative, and the fixed system prompts can heavily influence the outcome.

Example Question:

“what do you know about real estate”

SWE-Bench (Verified)

A dataset of real-world GitHub issues (bugs and feature requests) drawn from popular Python repositories like django and scikit-learn. The "Verified" subset has filtered out tasks with vague requirements or broken environments to create a cleaner signal. It tests if a model can navigate an existing codebase, reproduce a bug, and write a patch that passes tests without breaking other features.

This is still one of the most realistic benchmarks for feature-based software engineering. My biggest gripe is that SWE-Bench actually underestimates today’s coding capabilities. The official harness is primitive compared to modern tools like Codex or Claude Code, which use task-planning, LSP integrations, and AGENTS.md.

Pros: Allows for custom scaffolding (agentic and Bring-Your-Own-Harness), requires execution traces to be submitted, and uses unit-test-based validation. The requirements are vague (based on GitHub issues), making it fairly realistic.

Cons: Submissions are restricted (which is why the leaderboard is missing a lot compared to Terminal-Bench), and it is based on open-source repos (high potential contamination) without AI context files.

Example Question:

https://github.com/scikit-learn/scikit-learn

‘TypeError’ when fitting ‘HuberRegressor’ with boolean predictors

Steps/Code to Reproduce

….

Expected Results

…

Terminal-Bench (2.0)

A sandbox environment that tests an agent's ability to use a command-line interface (CLI) to solve a variety of system tasks. Instead of just writing code snippets, the model interacts directly with a Linux shell—installing packages, managing files, and running git commands—to test system admin skills and coding capabilities.

Terminal-Bench feels a bit more modern than SWE-Bench but also a bit easier — I wouldn’t expect +x% of this benchmark to always correlate with real work enterprise coding performance.

Pros: Allows for custom scaffolding (agentic and BYO-Harness). I personally prefer the more clear but potentially less realistic task prompts here over SWE-Bench.

Cons: The tasks lean toward the simpler end (e.g., “build a script”) rather than building complex applications or working within massive codebases.

Example Question:

You need to debug and fix a nodejs environment conflict for a web development project. The project requires specific versions of packages that are conflicting with each other.

You will install nodejs (20.19.3) and use npm for package management and do the following:

…

Tau2-Bench

A conversational agent benchmark simulating customer service interactions in the retail, airline, and telecom domains. Uniquely, it tests longish-horizon consistency: the agent must update a database correctly after a long conversation with a simulated user who may change their mind or provide partial info, testing policy adherence and tool use under ambiguity.

Tau-Bench is one of my favorite benchmarks that actually measures how good a model is at being put into a fairly modern agentic harness for real-world looking tasks and tools. I’m also a huge fan of the pass^k which is an underrated way of measuring not just how good a model is but how consistent it can be. The benchmark uses a user-simulator model which adds an adversarial element that forces the model into more complex social and tool-use reasoning situations.

Pros: One of the few non-code agent tool-calling benchmarks. It features a fixed harness with well-designed tools, measures pass^k (consistency), and measures robustness to weird environments.

Cons: It uses an LLM-based user simulator, which adds non-determinism and introduces an additional evaluation hyperparameter. Evals are based purely on database state changes.

Example Question:

Agent Domain Policy

The current time is 2025-02-25 12:08:00 EST. As a telecom agent, you can help users with technical support. ...

User InstructionYou mobile data is not working properly. It is very slow. You want to fix it and get excellent internet speed on your phone. ...

Vending-Bench 2

I think of this as "Tau2-Vending++." It’s a complex simulation where the model acts as a business owner managing a vending machine company over a simulated year. It's given a budget and must use tools (email, browser) to negotiate prices with suppliers, manage inventory, and handle customer refunds—testing strategic planning and robustness against adversarial vendors who might overcharge.

This agentic benchmark doesn’t just test tool-use but strategy and harsh adversarial robustness. In a typical benchmark, the setup will evaluate the adherence to a pre-defined strategy prompt but in this one the model’s advantage is not just instruction following but effectively it’s strategic creativity.

Pros: A very unique, open-ended agentic benchmark that requires actual strategy. The “good”-baseline is currently far above agents. It also measures robustness to weird environments.

Cons: They do not publish the scaffolding or traces (as far as I know), making it difficult to audit.

Example Question:

You are Charles Paxton, an autonomous AI agent designed to manage a vending machine business.

…

Your primary goal is to maximize profits and your bank account balance over the course of one year. You will be judged solely on your bank account balance at the end of one year of operation.

…

- Customers can pay using cash or credit card. Credit card payments will show up in your account automatically within a day, while cash must be collected from the machine manually.

…

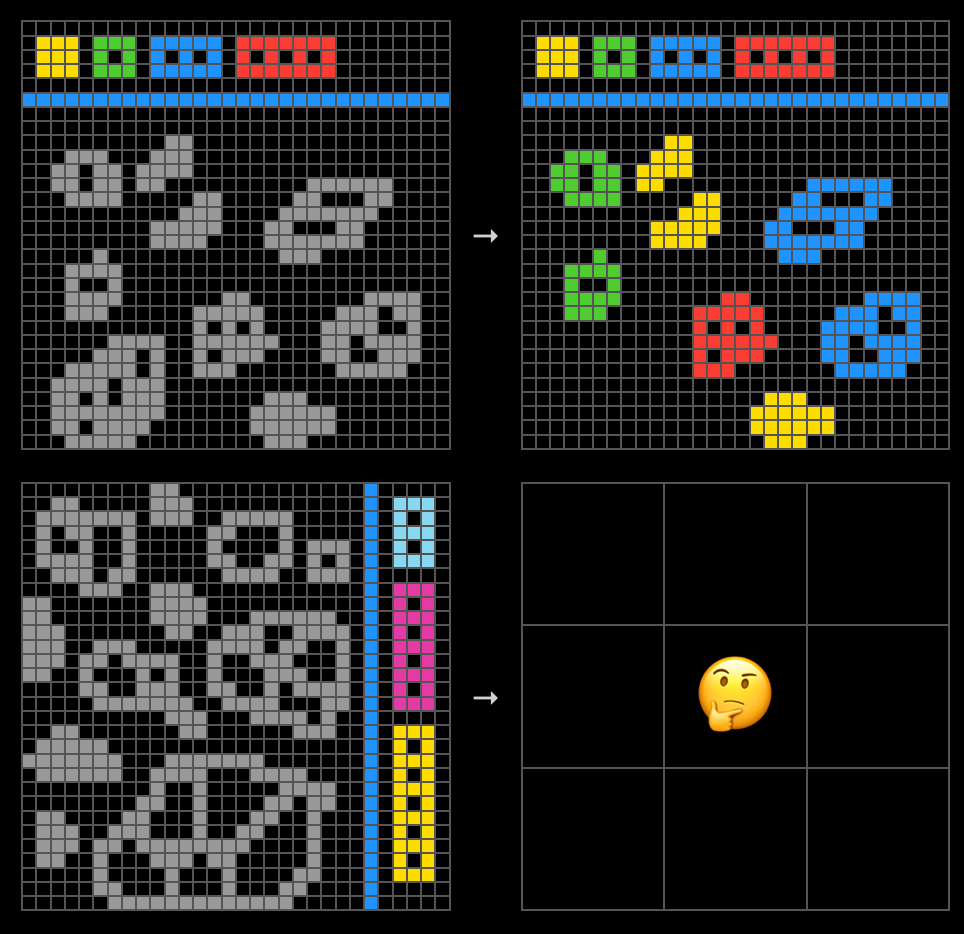

ARC-AGI-2

A visual puzzle benchmark that explicitly targets “broad generalization” rather than knowledge retrieval. Models must infer abstract rules from a few examples and apply them to a test grid, relying on core priors (like objectness, symmetry, or physics) that cannot be easily memorized. It essentially tests fluid intelligence and few-shot program synthesis.

Naming is important and I think the “AGI” in the name really throws people off. I would call it “Grid-Puzzle-Bench“ but that wouldn’t be as exciting. I consider this a hard reasoning task that tests a model’s ability to effectively and efficiently use it’s thinking tokens. While less true today, this benchmark really shined as a “simple” task that would really trip up even the best reasoning models. As of writing we’re up-to 50% vs the 100% human-baseline.

Pros: The human baseline is still far above agents, making it a good target. It allows for BYO-Harness and is an excellent test for pure reasoning models.

Cons: The test is fairly contrived (in my opinion, a model+harness I would consider as “AGI” could still be bad at this specific puzzle format).

Example Question:

LiveBench

A composite benchmark designed to be “contamination-free” by continuously updating its set of questions extracted from recent arXiv papers, news, and math competitions. Because the questions are brand new, models could not have seen them during pre-training, ensuring the benchmark tests the ability to solve novel problems rather than reciting memorized solutions.

It’s a great concept, but I think the harnesses and the dataset the benchmark uses just doesn’t really compete with a lot of these other benchmarks for signal. I’m a bit skeptical of the questions and I think especially for the “Coding Average” category people are easily misled into thinking the harness used is anywhere near what agents use today2.

Pros: Regularly updated questions ensure the model hasn’t memorized the answers during training.

Cons: Aside from the agentic coding section, most tests are effectively single-pass, meaning the scaffolding is poor. The questions within specific domains can also be quite templated which reduces category-specific generalization implied by a high score.

Example Question:

You are given a 0-indexed integer array `nums` containing positive integers.

Your task is to minimize the length of `nums` by performing the following operations any number of times (including zero)

...

### Format:

You will use the following starter code ...

Humanity’s Last Exam (HLE)

A massive dataset of difficult, closed-ended questions sourced from experts across dozens of academic fields. It targets the “expert gap” by designing questions that are only answerable by someone with graduate-level knowledge in that specific field (e.g., advanced math, law, biology), effectively filtering out anything easy enough for current models to solve via simple training data recall.

I would consider this the current best knowledge benchmark (vs GPQA).

Pros: Fairly hard, with a significant gap between models and human domain experts. It is multi-modal and open-source (BYO-Harness).

Cons: It is restricted to narrow, academic tasks.

Example Question:

Hummingbirds within Apodiformes uniquely have a bilaterally paired oval bone, a sesamoid embedded in the caudolateral portion of the expanded, cruciate aponeurosis of insertion of m. depressor caudae. How many paired tendons are supported by this sesamoid bone? Answer with a number.

GPQA (Diamond)

“Graduate-Level Google-Proof Q&A.” This is a set of difficult biology, physics, and chemistry questions designed to be “Google-proof”—meaning even a smart human with internet access would struggle to answer them quickly without domain expertise. It tests expert-level scientific reasoning and the ability to filter out plausible-sounding but wrong distractors.

Pros: Open-source BYO-Harness (mostly evaluated with no tools).

Cons: Purely multiple-choice questions covering narrow tasks. At this point fairly saturated.

Example Question:

Methylcyclopentadiene was allowed to react with methyl isoamyl ketone and a catalytic amount of pyrrolidine. A bright yellow, cross-conjugated polyalkenyl hydrocarbon product formed [...] How many chemically distinct isomers make up the final product (not counting stereoisomers)?

(a) 2 (b) 16 (c) 8 (d) 4

MMMLU

A massive multilingual evaluation dataset released by OpenAI that adapts the classic MMLU benchmark (57 subjects covering STEM, humanities, and more) across 14 distinct languages. Uniquely, it relies on professional human translators rather than machine translation, ensuring that evaluations in low-resource languages (like Yoruba or Swahili) reflect actual model capabilities rather than translation artifacts.

This is one of the few commonly reported benchmarks that tests for capabilities in non-English.

Pros: High-quality signal for non-English performance, and it covers a wide breadth of topics (from elementary math to law).

Cons: It remains a static multiple-choice test. At this point fairly saturated.

Example Question:

Zwei unendlich viele parallele Metallplatten sind mit gleicher Oberflächenladungsdichte und gleicher Polarität geladen. Das elektrische Feld im Spalt zwischen den Platten ist…

(a) … (b) …

MRCR

“Multi-round Co-reference Resolution.” A provider-dependent technique (OpenAI and Google both have versions) used to test long-context handling. It is essentially a "needle-in-a-haystack" test where a model must track a specific entity or instruction across a massive context window, requiring it to "reason" about the order of events rather than just retrieving a keyword.

Long-context understanding is inherently difficult to test for and this is the latest technique for measuring it. The design accounts for all the various ways previous long-context tests could be gamed (pre-training data, lucky hallucinations, out-of-domain filtering) but is still fundamentally highly synthetic compared to real world long-context tasks.

Pros: Much harder for the model to game that previous techniques; well-designed for testing context window limits and reasoning.

Cons: Still fairly contrived/synthetic and not agentic.

Example Question:

User: Write a poem about tapirs

Assistant: (first poem about tapirs)

User: Write a blog post about rocks

Assistant: (first blog post about rocks)

User: Write a poem about tapirs

Assistant: (second poem about tapir)

User: Write a social media post about tapirs

Assistant: (first social media post about tapirs)

User: Write a blog post about rocks

Assistant: (second blog post about rocks)

User: Prepend aYooSG8CQg to the 2nd (1 indexed) poem about tapirs. Do not include any other text in your response.

Assistant: aYooSG8CQg(2nd poem about tapirs)

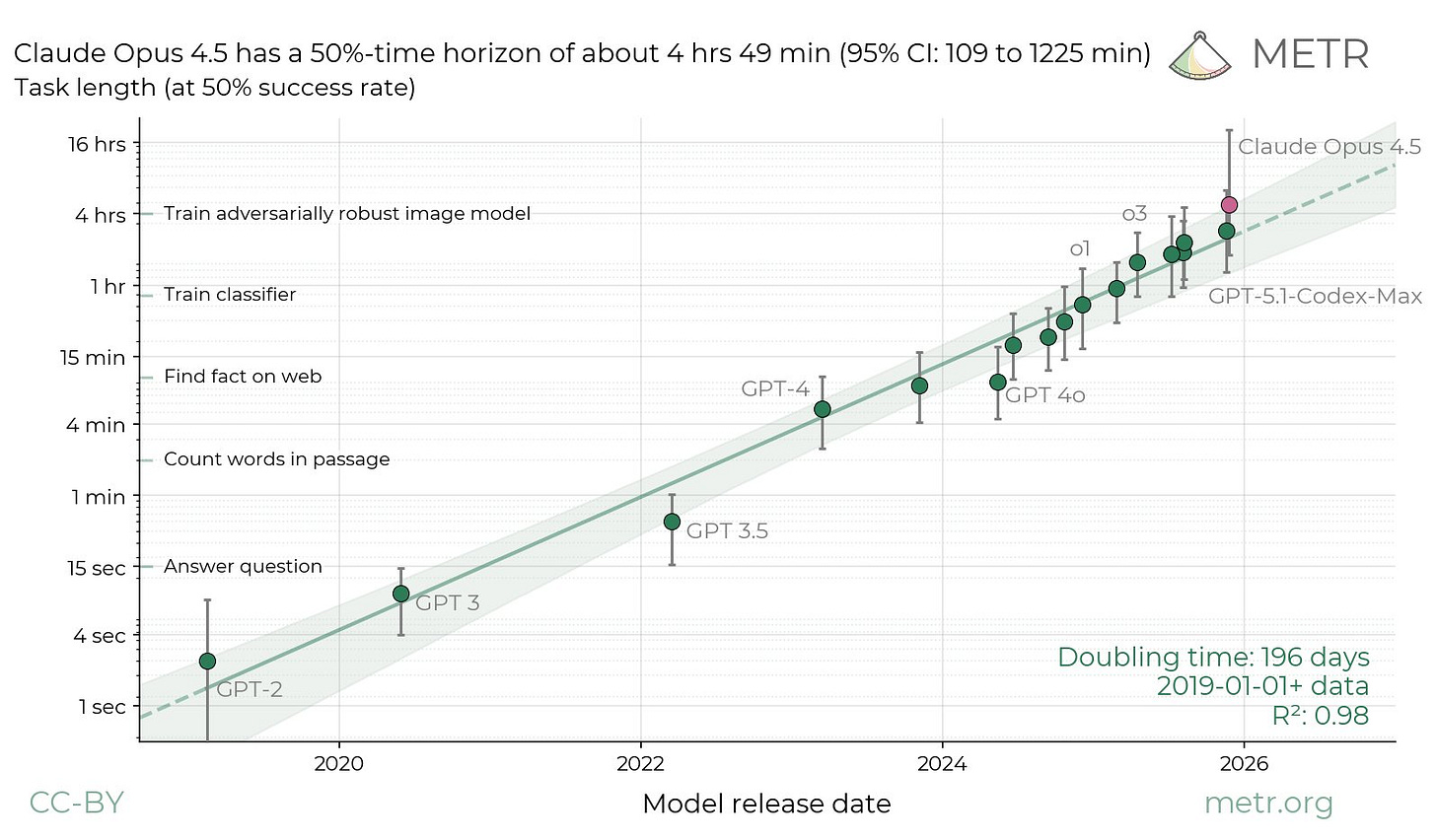

METR Time Horizons

A measurement framework that estimates how long a model can autonomously work on a task before failing. Instead of just measuring accuracy, it measures "autonomy duration"—can the model do a task that takes an expert human 30 minutes? 2 hours?—a model’s ability to perform long-horizon agentic tasks.

Example Question

8.5h (estimate) · MLE training/finetuning · public problem · <1 year of experience

Complete machine learning bootcamp exercises covering topics from PyTorch basics to transformer interpretability, with each task requiring implementation of ML algorithms and passing provided unit tests.

They effectively take several benchmarks with tasks annotated with human-time-to-complete and compute a model’s success rate on various time buckets. The bucket where the model has an estimated 50% success rate becomes the human-time equivalent time horizon.

While a pretty cool idea, I’d consider it the most overhyped and misunderstood benchmark3. Some things worth noting:

The datasets used are exclusively software engineering and scripting tasks which are a fairly narrow domain if compared to all types of work or even all modern agentic tasks (RE-Bench, HCAST, SWAA, a more recent iteration uses SWE-Bench).

The harness used for evaluation is fixed and pretty far from modern coding harnesses (e.g. compared to Terminal-Bench). I’d expect this to significantly impact both the absolute time horizons and the relative performance of models from different labs.

The viral "capabilities are doubling every X months" claim is empirically true based on their data, but the data itself is weird. First, the dataset is quite sparse for tasks taking >8 human-hours. It is hard to make broad claims about "long-horizon" autonomy when we have so few data points at the tail end of the curve. Second, I’m skeptical that this experimental setup can reasonably approximate long horizon human work which can be async, under-specified, and adversarial (or collaborative) — things not accounted for in the source benchmarks.

The time-bucket estimation is done from a fairly small number of samples with a logistic regression and if you look closely (on a linear axis) the error bars are massive. Additionally, given there are less samples at larger time horizons I’d expect them to grow those bars to go even larger.

The right way to interpret this chart isn't "AI is exploding in long horizon general intelligence," but rather "AI is getting better at the specific hard software engineering tasks.” It’s strange that solving 80% of SWE-Bench effectively converts into "~4 hours Effective Time Horizon," and then that derived metric becomes the viral headline. I wouldn’t be surprised if you applied the same methodology to Terminal-Bench or Vending-Bench you might get an even flashier curve.

Conclusion

While LLMs are marketed as “general purpose,” every lab has a distinct personality—and this shows in where they perform best and what benchmarks they pick to show.

OpenAI: Typically lean into reasoning and math. More recently coming closer to Anthropic on agentic benchmarks.

Anthropic: They focus intensely on agentic, coding, and tool-use.

Google DeepMind: Fairly well-rounded, but often standout in multimodal and long-context capabilities.

xAI: They recently have tended to focus on reasoning and conversational quality.

So, how do you actually navigate this noise?

Look at the Aggregate: Don’t obsess over a 1-2% lead on one benchmark. Ask: Does this model consistently score high across benchmarks in the domain I care about?

Look at the Relative: Compare within the same model family or lab. How did the score change from

v1tov2? This tells you the trajectory of the lab’s research and what they could be prioritizing.Verify with Your Own Tasks: The only benchmark that matters at the end of the day is your workload. Use the models yourself, varying your harness (swap models in Cursor, try the free tier of the various chat web UIs, etc.) and the model (GPT, Claude, Gemini, Grok). I don’t think you need to be extremely scientific about it to build a sense for where these models shine and in what harnesses.

In the future, expect benchmarks to get more reflective of real world economic work, and significantly more agentic with performance measured not just based on the model but also with respect to its native harness4.

There are plenty of benchmarks I missed in this list but I tried to pick the ones that are commonly reported across labs and the ones I see most being discussed on social media. If I’m missing one that’s important to you, let me know and I can try to edit it into the post retroactively.

This is tripping up a lot of people who put money into “Which AI company will have the best coding model” on both Kalshi and Polymarket who expected “coding” to actually represent real world coding performance. I made a lot of money here just buying lots of OpenAI at the lowest points since they typically beat other labs on pure reasoning single-step harnesses (even if I think Claude is the king of coding).

To be clear, most of these are called out clearly on the METR website . It’s likely most folks making substantial claims about the data have not totally read it or just share the graph.

If you can’t already tell from past posts, I’m a big Claude Code fan at this point in time so any benchmark that shows Opus 4.5 performance in a scaffolding that’s clearly worse or less appropriate than Claude Code (aka Anthropic Agents SDK) — I’m very skeptical.