Taste Is Not a Moat

Why the last human edge is already being industrialized.

I used to write the design while AI coded the software. Architecture decisions, API contracts, data models on my side; implementation on its side. Fast forward a few months and more and more the model now handles both, because it’s more right than wrong. The “outer loop” of system design, the thing that engineers would do while AI wrote the the code, turned out to be just another task it would absorb.

Over the past year, Tech Twitter has mostly converged on the same answer to this problem1. As AI eats execution, taste is the moat.

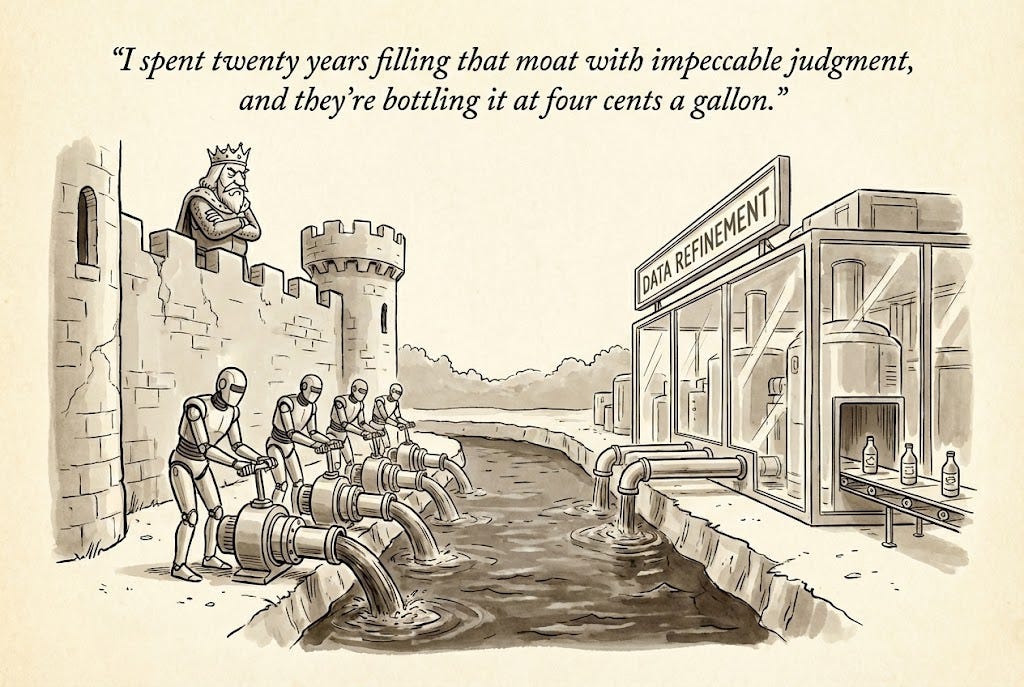

And while they’re right about taste mattering. I’m less sure about the moat part. A moat is something you build once and defend. Taste feels more like alpha2: a decaying edge, only valuable relative to a rising baseline. And that baseline is rising faster than many realize.

In this post, I wanted to focus on taste; how it changes the human role and questions around who owns it.

Where the baseline is now

Every domain has a threshold where AI crosses from “clearly worse” to “good enough to fool experts.” Those thresholds are falling fast as the models get better and organizations get better at providing the right context.

2024: AI could autocomplete but not architect. Copilot suggestions had a higher churn rate than human code. AI-generated marketing copy was formulaic and easy to spot. AI-generated playlists were novelties, not chart contenders. AI hiring meant keyword-matching resumes with well-documented bias. The consensus across every domain was the same: AI can handle the grunt work, but taste, judgment, and design are ours.

2025: “Vibe coding” became mainstream. Consumers rated AI marketing copy better than professional copywriters. Music listeners couldn’t distinguish AI music from human music. Frontier models are matching human experts on nearly half of tasks across occupations, completing them 100x faster and 100x cheaper. In twelve months, “AI can’t do X” became “AI does X better than most people” in domain after domain.

2026: The majority of US developers use AI coding tools daily. AI-generated music accounts for over a third of daily uploads on major platforms. The question is no longer whether AI can match human taste in a given domain, but how long until it does in yours.

This is why I see taste as alpha, not a moat. My judgment is only valuable relative to what AI can do by default, and that default resets every few months.

If taste decays, the question stops being “do you have it?” and starts being “how fast can you get it into a system before the baseline catches up?”

How taste is reshaping roles

Even as taste decays as a durable advantage, it’s becoming the primary thing organizations pay humans to do (on top of just having the agency to use AI to do their job)3.

Having taste matters just as much as being able to communicate it. Out of the box, many of us can’t fully articulate why we prefer one design over another, why this copy lands and that one doesn’t, why this architecture will scale and that one won’t. The knowledge is tacit, embodied in instinct rather than rules. However, jobs are shifting from executor to taste extractor: someone whose primary skill is getting their judgment into the system.

The best hire for an AI-native marketing team isn’t the person with the most original campaign ideas (despite their ‘taste moat’). It also isn’t the person with mediocre instincts who happens to be good at prompting ChatGPT. It’s the person with N years of pattern recognition about what converts, what falls flat, and why, who can turn that into something a system can use.

Their day-to-day looks nothing like a traditional marketer’s. They spend the morning reviewing AI-generated campaign variants, not writing them. They run A/B interviews against their own preferences to build an Essence document for the brand’s voice. They flag the three outputs out of twenty that feel subtly wrong and articulate what’s off: too eager, wrong register for the audience, buries the value prop. That articulation becomes a constraint the system applies to the next hundred outputs. By afternoon they’re not writing copy; they’re tuning the machine that writes copy.

It’s not “creativity” in the traditional sense and it’s not “prompt engineering” in the shallow sense. Taste extraction builds a persistent model of your judgment that compounds across every output after it. It’s the ability to encode experienced judgment into a system that scales it.

The pattern applies to plenty of taste-heavy roles:

Designers stop pushing pixels and start curating.

Recruiters stop screening and start calibrating for “high potential”.

Product managers stop writing specs and start steering batches of features.

…

How to extract your taste (before someone else does)

Your taste can be a black box. You know what good looks like when you see it. You probably can’t explain why. Extraction is about surfacing that tacit judgment so a system can act on it and so you can leverage up on your productivity.

Without extraction, your outcomes with AI drift. Prompt the same task across sessions without a persistent reference document and the AI reconstructs from training data priors each time; the output flattens toward the sloppy median4.

There are a couple ways I’ve been experimenting with getting better at this. They apply across domains, not just code.

A/B interviews

Have AI present you with paired options and ask which you prefer and why. Your explanations, especially the ones you struggle to articulate, are the signal. After 10-15 rounds, the model synthesizes your preferences into a document it references for future work.

Given this [style guide / doc / brief], interview me using A/B examples to help refine the [tone / style / design] guidance. Present me with two options for a [headline / paragraph / layout / architecture]. First, critique both options. Then ask me which I prefer and why. Use my answers to write a 1-page “Essence” document summarizing my taste in this domain.

The Essence document becomes a reusable asset. I’ve done this for writing style, UI design preferences, and code architecture patterns. I now run this process for every new domain before generating anything significant.

Ghost writing

Increasingly every remaining task I do by hand, I also run AI on the same task in the background with minimal context. If I’m writing a blog post, I have AI write one too before I start. If I’m designing an architecture, I have AI propose one in parallel. Then I compare.

Here is the [requirements doc / ticket / brief]. Propose a full [architecture / system design / data model]. Include your reasoning for each major decision.

The value isn’t in which draft is better. It’s in where I flinch. The moments where the AI output feels off, where the slop is obvious to me but hard to name, those reactions are taste made visible. And the places where I’m contributing something the model didn’t, those are my actual alpha.

Over time, the flinch points become encodable. I note them down, turn them into constraints, and feed them back into the system. This does two things at once: it helps me identify where my taste actually lives, and it gives me the language to express preferences I previously couldn’t articulate. The gap between my draft and the AI’s draft shrinks, but my ability to direct the output sharpens because I’m forced to make the tacit explicit.

External reviews

Your own taste has blind spots. One way I augment mine is by extracting the approximate taste of other people and running it through AI.

In practice, this means using tasks (aka dynamic subagents) in Claude Code that represent specific perspectives5:

An audience segment I’m writing for.

A manager or coworker whose judgment I trust.

A writer or brand whose voice I admire.

I feed them real context: Zoom transcripts from calls, written feedback I’ve received, published work I want to learn from. Then I ask each agent to independently review whatever I’m building or writing.

Use a task to read the attached [transcript / feedback thread / writing samples] from [person or role]. Extract their values, preferences, and recurring critiques. Then review this [draft / design / architecture] as if you were that person. Flag what they’d push back on, what they’d approve of, and what they’d want to see more of.

It’s not a replacement for real feedback, but it catches the obvious misses before I ask for it. And it compounds: every round of external review surfaces blind spots in my own taste that I can then fold into my Essence documents and constraints. This also means the real feedback I get back is higher-signal too.

When platforms farm taste at scale

Everything above is about extracting your taste to stay ahead. But there’s a catch: you’re not the only one extracting.

TikTok doesn’t need any individual user to have great taste. It collects millions of low-signal interactions (swipes, watch time, replays, skips) and synthesizes something that functions like taste at industrial scale. No single swipe is valuable. In aggregate, those micro-signals train a recommendation system that N billion people spend hours inside daily. YouTube, Spotify, Instagram, Netflix: every app with an algorithmic feed is essentially a taste factory.

The factory doesn’t just curate what humans make; it increasingly curates what AI makes, selecting for whatever the aggregate says “good” looks like. The extraction workflow that empowers you at the role level simultaneously trains these platforms. Your prompts, preferences, and clicks all teach systems that then compete with your own judgment. And this doesn’t require anyone to train directly on your data. It happens indirectly: your taste-informed outputs perform well, get clicked, shared, imitated, and that performance signal feeds back into the next generation of models and recommendation systems. The platform learns what “good” looks like from millions of people, then serves it back at scale without needing any of them individually.

In the extreme, platforms could become the primary owners of taste, not individuals. Our role shifts from having taste to feeding it. The system doesn’t need to match your judgment on any specific decision; it just needs enough signal from enough people to converge on something the market accepts. The “platform” here might not even be the feeds, but could be the labs and token producers.

Open questions

Can taste be taught? If it develops through some opaque function of experience and exposure, what happens to people who haven’t had the right experiences? Dario warned about AI “slicing by cognitive ability,” creating stratification based on traits harder to change than specific skills6. Taste is a version of that divide.

Do taste roles mean more hiring or less? Right now, the pattern is fewer people with more leverage: marketing teams shrink, one designer steers what five used to produce. But if the job is encoding judgment, don’t you actually want more people sourcing taste from more angles? A single extractor’s blind spots become the system’s blind spots.

Who wins the taste race: individuals or platforms? Every extraction technique in this post works in both directions. You encode your judgment to scale your leverage; the platform collects that same signal to scale without you. If the platform can interview me better than I can articulate myself, farm preferences from millions of users simultaneously, and apply the aggregate at near-zero cost, does individual taste become a contribution to someone else’s moat?

If so, will people accept taste farming as work? If platforms need human micro-signals to train their systems, does “pay per swipe” become a job category? If AI results in far fewer jobs, is this the remaining option? Who reaps the majority value of individual taste at that point?

The people calling taste a moat are right that it matters. They’re wrong that it’s yours to keep. The more I practice articulating my own taste, the less sure I become that it’s durable.

A moat, in business strategy, is a structural advantage that’s hard to replicate: a patent, a network effect, a regulatory lock-in. You build it once and competitors can’t easily cross it. Alpha, in finance, is the return you earn above what the market gives you for free, the gap between a hedge fund’s performance and a simple index fund. The key difference: a moat persists by design, but alpha decays. The more people discover the same strategy, the more the market absorbs it, and the edge shrinks. Taste behaves like alpha, not a moat. Your judgment is only valuable relative to what AI produces by default, and that default gets better on its own.

I say this from the perspective of someone who works for a fairly AI-native organization and spends time with a lot of people who are in the SF AI bubble. I recognize that there’s still quite a few jobs out there that are now trivially done by AI but are still being done by humans as AI transformation takes time to diffuse to the rest of the world.

Two things happen at once. First, without externalized standards, AI outputs regress to the distribution it was trained on. Each new session starts from that distribution’s center, not from where you left off, so quality flattens toward the median. Second, that median itself keeps rising. The taste you encode today, your Essence documents, your constraints, your feedback, eventually gets absorbed into training data for the next generation of models. What was your alpha becomes the new default. This doesn’t even require the model to train on your prompts or data directly; it happens indirectly through how your taste-informed outputs perform in the world, what gets clicked, shared, purchased, and imitated, which all feed back into the next training distribution. This is why taste behaves like alpha: your edge above the median is real but temporary, because the median is a moving target that absorbs the signal you feed it.

It’s key that you use sub-agents or tasks for this workflow because you want a fresh, unbiased session/context-window to review the work.

I love this post. I think it's spot-on for where I think things are headed.

TikTok indeed is an existence proof that taste can be captured digitally. Where we converge at an equilibrium may literally just be an oligopoly of models where many implicit assumptions are embedded, with different "tastes" which cater to some specific subsegment of the population. Kinda like politics if you think about it with different parties and "taste"

This is grossly over-engineered. Taste isn’t a system or checklist and it’s certainly can’t be taught or given to someone.

Even someone who’s put in their mythical “10,000” hours isn’t guaranteed to have any taste as we all know a millionaire (or billionaire) who has none.

Taste is a feeling. And some folks have it and some will never have it. That’s why we have tastemakers and everyone else enjoys their work.

Trying to distribute it broadly or teach it is exactly the opposite of what it is. It’s impossible to capture in a blog post or put in a slogan or marketing campaign. It just… is.

They either have it or they don’t.