Building Multi-Agent Systems (Part 3)

Updated methods for scaling scripting-based agents to handle complex problems reliably.

It’s now been over two years since I started working seriously with agents, and if there is one constant, it is that the "meta" for building them seems to undergo a hard reset every six months.

In Part 1 (way back in December 2024), we were building highly domain-specific multi-agent systems. We had to augment the gaps in model capabilities by chaining together several fragile sub-agent components. At the time, it was unclear just how much raw model improvements would obsolete those architectures.

In Part 2 (July 2025), LLMs had gotten significantly better. We simplified the architecture around "Orchestrator" agents and workers, and we started to see the first glimmer that scripting could be used for more than just data analysis.

Now, here we are in Part 3 (January 2026), and the paradigm has shifted again. It is becoming increasingly clear that the most effective agents are solving non-coding problems by using code, and they are doing it with a consistent, domain-agnostic harness.

In this post, I want to provide an update on the agentic designs I’ve seen (from building agents, using the latest AI products, and talking to other folks in agent-valley1) and break down how the architecture has evolved yet again over the past few months.

What’s the same and what’s changed?

We’ve seen a consolidation of tools and patterns since the last update. While the core primitives remain, the way we glue them together has shifted from rigid architectures to fluid, code-first environments.

What has stayed the same:

Tool-use LLM-based Agents: We are still fundamentally leveraging LLMs that interact with the world via “tools”.

Multi-agent systems for taming complexity: As systems grow, we still decompose problems. However, the trend I noted in Part 2 (more intelligence means less architecture) has accelerated. We are relying less on rigid “assembly lines” and more on the model’s inherent reasoning to navigate the problem space.

Long-horizon tasks: We are increasingly solving tasks that take hours of human equivalent time. Agents are now able to maintain capability even as the context window fills with thousands of tool calls. The human-equivalent time-horizon continues to grow2.

What is different:

Context Engineering is the new steering: It is becoming increasingly less about prompt, tool, or harness “engineering” and more about “context engineering” (organizing the environment). We steer agents by managing their file systems, creating markdown guide files, and progressively injected context.

Sandboxes are default: Because agents are increasingly solving non-coding problems by writing code (e.g., “analyze this spreadsheet by writing a Python script” rather than “read this spreadsheet row by row”), they need a safe place to execute that code. This means nearly every serious agent now gets a personal ephemeral computer (VM) to run in.3

Pragmatic Tool Calling: We are moving toward programmatic tool calling where agents write scripts to call tools in loops, batches, or complex sequences. This dramatically improves token efficiency (the agent reads the output of the script, not the 50 intermediate API calls) and reduces latency.

Domain-agnostic harnesses: As models improve, the need for bespoke, product-specific agent harnesses is vanishing. For the last several agents I’ve built, it has been hard to justify maintaining a custom loop when I can just wrap a generic implementation like Claude Code (the Agents SDK). The generic harness is often “good enough” for 90% of use cases.

The Updated Multi-Agent Architecture

As a side effect of these changes, the diverse zoo of agent architectures we saw in 2024/2025 is converging into a single, dominant pattern. I’ll break this down into its core components.

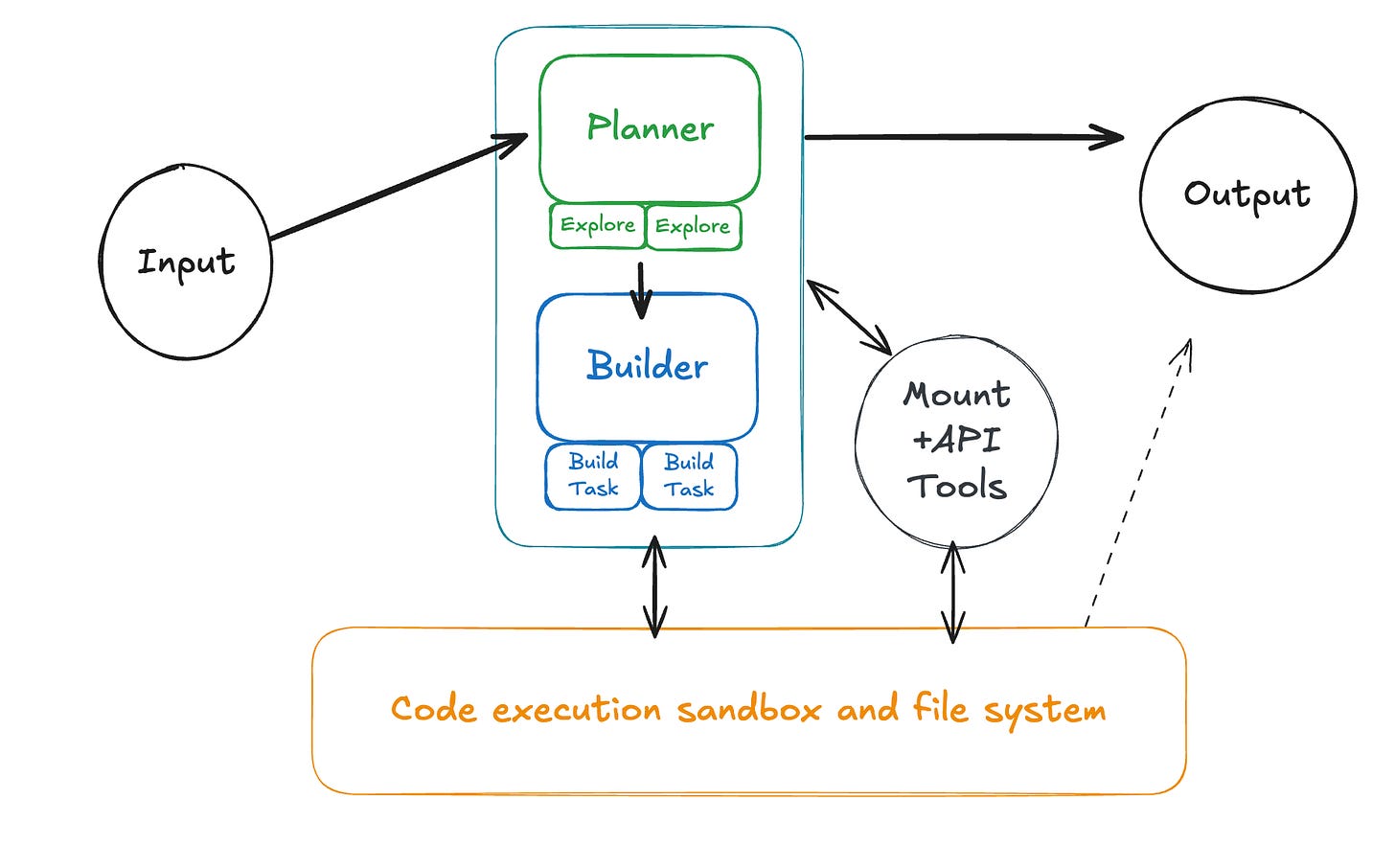

Planning, Execution, and Tasks

One of the largest shifts in the last 18 months is the simplification and increased generalizability of subagents. In the past, we hand-crafted specific roles like "The SQL Specialist" or "The Researcher." Today, we are starting to see only see three forms of agents working in loops to accomplish a task:

Plan Agents — An agent solely tasked with discovery, planning, and process optimization4. It performs just enough research to generate a map of the problem, providing specific pointers and definitions for an execution agent to take over.

Execution Agents — The builder that goes and does the thing given a plan. It loads context from the pointers provided by the planner, writes scripts to manipulate that context, and verifies its own work.

Task Agents — A transient sub-agent invoked by either a plan or execution agent for parallel or isolated sub-operations. This might look like an "explorer" agent for the planner or a "do operation on chunk X/10" for the execution agent. These are often launched dynamically as a tool-call with a subtask prompt generated on the fly by the calling agent.

This stands in stark contrast to the older architectures (like the "Lead-Specialist" pattern I wrote about in Part 2), where human engineers had to manually define the domain boundaries and responsibilities for every subagent.

Agent VMs

These new agents need an environment to manage file-system context and execute dynamically generated code, so we give them a VM sandbox. This significantly changes how you think about tools and capabilities.

Core VM Tool Design

To interact with the VM, there is a common set of base tools that have become standard5 across most agent implementations:

Bash — Runs an arbitrary bash command. Models like Claude often make assumptions about what tools already exist in the environment, so it is key to have a standard set of unix tools pre-installed on the VM (python3, find, etc.).

Read/Write/Edit — Basic file system operations. Editing in systems like Claude Code is often done via a

replace(in_file, old, new)format which tends to be more reliable way of performing edits.Glob/Grep/LS — Dedicated filesystem exploration tools. While these might feel redundant with

Bash, they are often included for cross-platform compatibility and as a more curated, token-optimized alias for common operations.

These can be deceptively simple to define, but robust implementation requires significant safeguards. You need to handle bash timeouts, truncate massive read results before they hit the context window, and add checks for unintentional edits to files.

Custom Tool Design

With the agent now able to manipulate data without directly touching its context window or making explicit tool calls for every step, you can simplify your custom tools. I’ve seen two primary types of tools emerge:

"API" Tools — These are designed for programmatic tool calling. They look like standard REST wrappers for performing CRUD operations on a data source (e.g.,

read_item(id)rather than a complexsearch_and_do_thing_with_ids(...)). Since the agent can compose these tools inside a script, you can expose a large surface area of granular tools without wasting "always-attached" context tokens. This also solves a core problem with many API-like MCP server designs."Mount" Tools — These are designed for bulk context injection into the agent's VM file system. They copy over and transform an external data source into a set of files that the agent can easily manipulate. For example,

mount_salesforce_accounts(...)might write JSON or Markdown files directly to a VM directory like./salesforce/accounts/6.

Script-friendly Capabilities

A script-powered agent also makes you more creative about how you use code to solve non-coding tasks. Instead of building a dedicated tool for every action, you provide the primitives for the agent to build its own solutions:

You might prefer the agent build artifacts indirectly through Python scripts (PowerPoint via python-pptx) and then run separate linting scripts to verify the output programmatically, rather than relying on a black-box or hand-crafted

build_pptx(...)tool.You can give the agent access to raw binary files (PDFs, images) along with pre-installed libraries like

pdf-decodeorOCRtools, letting it write a script to extract exactly what it needs instead of relying on pre-text-encoded representations.You can represent complex data objects as collections of searchable text files—for example, mounting a GitHub PR as

./pr/<id>/change.patchand./pr/<id>/metadata.jsonso the agent can use standardgreptools to search across them.You might use a “fake” git repository in the VM to simulate draft and publishing flows, allowing the agent to commit, branch, and merge changes that are translated into product concepts.

You can seed the VM with a library of sample Bash or Python scripts that the agent can adapt or reuse at runtime, effectively building up a dynamic library of “skills”.

Context Engineering

Context engineering (as opposed to tool design and prompting) becomes increasingly important in this paradigm for adapting an agnostic agent harness to be reliable in a specific product domain.

There are several great guides online now so I won’t go into too much detail here, but the key concepts are fairly universal. My TLDR is that it often breaks down into three core strategies:

Progressive disclosure — You start with an initial system prompt and design the context such that the agent efficiently accumulates the information it needs only as it calls tools.

You can include just-in-time usage instructions in the output of a tool or pre-built script. If an agent tries

api_call(x)and fails, the tool output can return the error along with a snippet from the docs on how to use it correctly.You can use markdown files placed in the file system as optional guides for tasks. A

README.mdin the VM root lists available capabilities, but the agent only reads specific files likedocs/database_guide.mdif and when it decides it needs to run a query.

Context indirection — You leverage scripting capabilities to let the agent act on context without actually seeing it within its context window.

Instead of reading a 500MB log file into context to find an error, the agent writes a

greporawkscript to find lines matching “ERROR” and only reads the specific output of that script.You can intercept file operations to perform “blind reads.” When an agent attempts to read a placeholder path like

./articles/<topic>.txt, the harness intercepts this write, performs a search, and populates the file with relevant snippets just in time.

Simplification — You use pre-trained model priors to reduce the need for context and rely more on agent intuition.

If you have a complex internal graph database, you can give the agent a

networkx-compatible wrapper. The model already knows how to usenetworkxperfectly, so zero-shot performance is significantly higher than teaching it a custom query language.If your system uses a legacy or obscure configuration format (like XML with custom schemas), you can automatically convert it to YAML or JSON when the agent reads it, and convert it back when the agent saves it.

TODOs, Reminders, and Compaction

For agents that need to perform increasingly long-running tasks, we still can’t completely trust the model to maintain focus over thousands of tokens. Context decay is real, and status indicators from early in the conversation often become stale. To combat this, agents like Claude Code often use three techniques to maintain state:

Todos — This is a meta-tool the agent uses to effectively keep a persistent TODO list (often seeded by a planning agent). While this is great for the human-facing UX, its primary function is to re-inject the remaining plan and goals into the end of the context window, where the model pays the most attention.7

Reminders — This involves the harness dynamically injecting context at the end of tool-call results or user messages. The harness uses heuristics (e.g., "10 tool calls since the last reminder about X" or "user prompt contains keyword Y") to append a hint for the agent. For example:

if user_focus.contains("checkout-button"); tool_result += "<hint>The user’s focus is currently on the checkout button component.</hint>"Automated Compaction — At some point, nearly the entire usable context window is taken up by past tool calls and results. Using a heuristic, the context window is passed to another agent (or just a single LLM call) to summarize the history and "reboot" the agent from that summary. While the effectiveness of resuming from a summary is still somewhat debated, it is better than hitting the context limit, and it works significantly better when tied to explicit checkpoints in the input plan.

Agent Checkup

If you built an agent more than six months ago, I have bad news: it is probably legacy code. The shift to scripting and sandboxes is significant enough that a rewrite is often better than a retrofit.

Here is a quick rubric to evaluate if your current architecture is due for a refactor:

Harness: Are you maintaining a domain-specific architecture hardcoded for your product? Consider refactoring to a generic, agnostic harness that delegates domain logic to context and tools, or wrapping a standard implementation like the Agents SDK.

Capabilities: Are your prompts cluttered with verbose tool definitions and subagent instructions? Consider moving that logic into “Skills” (markdown guides) and file system structures that the agent can discover progressively.

Tools: Do you have a sprawling library of specific tools (e.g.,

resize_image,convert_csv,filter_logs)? Consider deleting them. If the agent has a sandbox, it can likely solve all of those problems better by just writing a script.

Open-Questions

We are still in the early days of this new “agent-with-a-computer” paradigm, and while it solves many of the reliability issues of 2025, it introduces new unknowns.

Sandbox Security: How much flexibility is too much? Giving an agent a VM and the ability to execute arbitrary code opens up an entirely new surface area for security vulnerabilities. We are now mixing sensitive data inside containers that have (potentially) internet access and package managers. Preventing complex exfiltration or accidental destruction is an unsolved problem.

The Cost of Autonomy: We are no longer just paying for inference tokens; we are paying for runtime compute (VMs) and potentially thousands of internal tool loops. Do we care that a task now costs much more if it saves a human hour? Or are we just banking on the “compute is too cheap to meter” future arriving faster than our cloud bills?

The Lifespan of “Context Engineering”: Today, we have to be thoughtful about how we organize the file system and write those markdown guides so the agent can find them. But is this just a temporary optimization? In six months, will models be smart enough (and context windows cheap enough) that we can just point them at a messy, undocumented data lake and say “figure it out”?

My new meme name for the SF tech AI scene, we’ll see if it catches on.

I actually deeply dislike how this is often evidenced by METR Time Horizons — but at the same time I can’t deny just how far Opus 4.5 can get in coding tasks compared to previous models.

See also Davis’ great post:

You can see some more details on how planning and execution handoff looks in practice in Cursor’s Scaling Agents (noting that this browser thing leaned a bit marketing hype for me; still a cool benchmark and technique) and Anthropic’s Effective harnesses for long-running agents.

I’m a bit overfit to Claude Code-style tools (see full list here), but my continued understanding is that they fairly similar across SDKs (or will be).

Anthropic calls this “structured note taking” and Manus also discusses this in its blog post.

Really enjoyed this piece. The observation about repeated architectural refactors as agent count increases feels particularly important.

One pattern we’re seeing across teams is that as soon as agents start modifying shared systems, the failure modes shift from “did the model reason correctly?” to “did the system execute correctly?”

Ordering of actions, retries, partial failures, and cross-tool state divergence become the real bottlenecks. Context improves reasoning, but it doesn’t automatically guarantee coherent execution.

Wonder if you’ve seen similar execution-level issues as you scale agent workflows. It feels like there may be a missing coordination layer emerging in the stack.

This is a really crisp synthesis. You’re clearly tracking capability drift rather than just tool churn, and the way you frame “agents solving non-coding problems by writing code” matches what a lot of us are seeing in practice. The through-line from 2024 → 2026 feels accurate rather than hindsight-polished.

What’s working well

A few things you’re doing here that are especially strong:

• Separation of intent vs. execution — The Planner / Execution / Task Agent split keeps cognition clean without freezing it into brittle roles.

• Code-first sandboxes as a primitive — Treating the VM as the context substrate (not just a tool target) is the key insight of this era.

• Context engineering over prompt engineering — Filesystem-mediated context, mounts, and progressive disclosure scale far better than ever-larger prompts.

• Generic harnesses winning — Your point about wrapping something like Claude Code instead of maintaining bespoke loops is exactly where leverage has moved.

All of that lines up with the broader convergence we’re seeing.

Where authority becomes implicit (the quiet shift)

This new paradigm also introduces a subtle but important shift:

As soon as an agent gets a sandbox + scripting + mounted tools, authority is no longer defined by prompts or tool descriptions — it’s defined by what the runtime exposes.

In your architecture, authority is currently implicit in places like:

• Which binaries and libraries exist in the VM

• Which “API” and “Mount” tools are callable from scripts

• How long the VM lives and what state persists

• Whether spawned Task Agents inherit the same environment

This is where most modern agent systems quietly cross from capable to ambient authority — not because of bad design, but because the control surface moved.

Agent Permission Protocol overlay (minimal, non-disruptive)

Below is a clean APP overlay that fits exactly into the architecture you described, without changing the agentic patterns you like.

Finding

Execution Agents and Task Agents can currently invoke VM actions, scripts, and mounted APIs based on availability rather than an explicit, time-scoped grant.

Risk

• Authority silently accumulates as sandboxes get richer

• Task Agents can become confused deputies

• Long-running jobs outlive their original intent

• Auditing reduces to “what happened” instead of “what was authorized”

Recommendation

Introduce a sealed permission policy gate between planning and execution, and again before any sandbox action.

Concretely:

1. Planner → Issuer

• Planner produces intent + required capabilities (not tools).

2. Issuer

• Issues a permission policy scoped to:

• capabilities (e.g. read_fs:/data, run_python, api:salesforce.read)

• audience (Execution Agent ID or Task Agent ID)

• TTL (minutes, not session-length)

• nonce (single-use or bounded replay)

3. Sealer

• Sign-then-encrypt the policy.

4. Execution Agent / Task Agent (Presenter)

• Presents the sealed policy before any VM or API execution.

5. Verifier (outside the model)

• Deterministically verifies:

• signature

• expiration

• audience binding

• replay

• Exposes only the allowed VM capabilities and tools.

6. Executor

• Runs code with a capability-scoped environment.

7. Audit log

• Records verification decision + executed actions.

This matches the APP flow exactly and keeps intelligence and authority cleanly separated .

⸻

Revised execution flow (with APP inserted)

• User request arrives

• Planner Agent

• Discovers context

• Outputs intent + capability needs

• APP Issuer / Sealer

• Creates sealed, time-bound permission policy

• Execution Agent

• Presents policy

• APP Verifier

• Validates (fail-closed)

• Exposes scoped VM + tools

• Executor

• Runs scripts

• Spawns Task Agents with their own derived policies

• Audit

• Logs policy + actions

Nothing about your planning, scripting, or context engineering changes — only when execution is allowed.

Curious — how are you securing this today?

A few lightweight questions, just to understand how you’re thinking about it now:

1. Where is authority actually enforced today — inside the agent loop, at the VM boundary, or at an API gateway?

2. When a Task Agent spins up, does it inherit the full sandbox, or a reduced capability set?

3. Do sandboxes expire automatically, or can long-running jobs continue indefinitely?

4. If a script calls an internal API in a loop, what stops it from accessing adjacent endpoints?

5. Is there a single place you can answer: “What was this agent explicitly allowed to do?”

6. If a permission artifact were replayed tomorrow, would anything detect or block that?

No wrong answers here — these are exactly the questions this new paradigm forces.

This is a solid map of where agent design has landed in 2026. If you want, I’m happy to:

• Sketch a concrete APP policy for one of your example workflows

• Walk through how to scope a VM as a capability, not an environment

• Share a reference pattern for Task Agent delegation without ambient authority

Great post — this is the right level of abstraction for where the field actually is.